Race, ethnicity, poverty factor into the re-segregation of Arizona’s schools

Source: AZEDNEWS

Arizona students from different racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to go to school together now than 25 years ago, according to new research by an Arizona State University professor.

This increasing segregation is cause for concern, said Dr. Jeanne Powers, associate education professor atASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College.

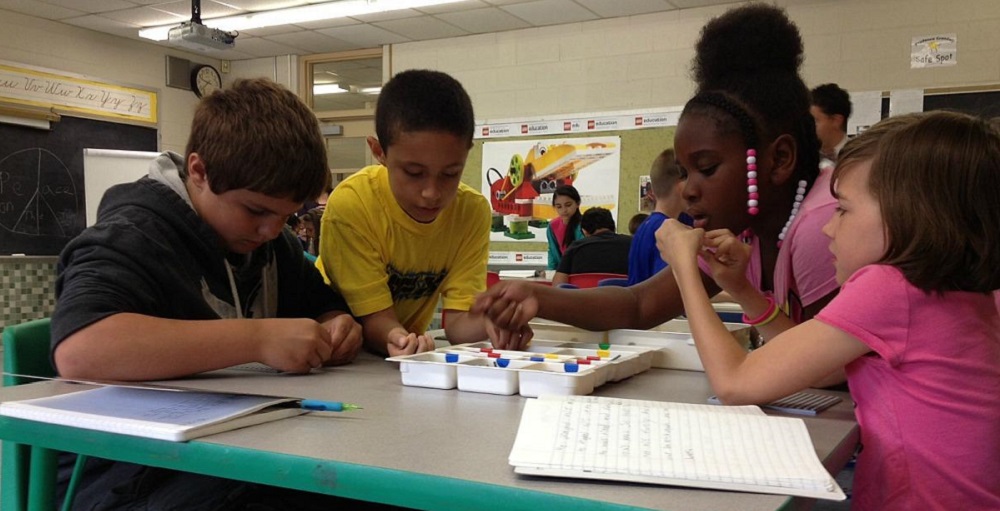

“American society is becoming increasingly diverse and schools are one of the most important places where students are exposed to peers with a range of backgrounds and experiences,” Powers said. “Our public schools are where our children learn to navigate an increasingly multicultural and globalized society.”

Powers presented her research on de facto segregation – segregation that occurs by practice, not established by law – to education leaders from around the state on Sept. 5. Earlier that week, the U.S. Department of Education projected that America’s public school students would be majority minority this fall.

Arizona’s PreK-12 public schools have been majority minority since 2004, according to the Arizona Minority Student Progress Report 2013: Arizona in Transformation.

“The students in our classroom are the new mainstream,” said Dr. Kent Paredes Scribner, superintendent ofPhoenix Union High School District. “It’s not some social justice rallying cry – it’s math.”

In Phoenix Union, 81 percent of its 27,031 students are Latino, nine percent are Black, five percent are White, three percent are Asian-American, two percent are Native American, and 40 percent of students identify themselves as from more than one racial or ethnic group, Scribner said.

Research on desegregation programs indicates that students who attend integrated schools are able to communicate and make friends across racial lines, they value working and living in diverse settings, and they tend to be more open-minded and accepting of racial and cultural differences, Powers said.

In 1990, the majority of Arizona’s public school students were White, but by 2012, Latino students were the majority. Yet the racial/ethnic composition of public schools statewide does not reflect that.

Dr. Jeanne Powers

“While the percentage of White students in Arizona has decreased since 1990, White students remain racially isolated so that in 2012 the typical White student attended a school that was 61 percent white, even though they comprised only 42 percent of the state’s public school students,” Powers said.

The average Latino student goes to a school that is 61 percent Latino, and the average Native American student goes to a school that is 49 percent Native American.

“Students who attend predominantly minority schools tend to have less access to important educational resources such as experienced teachers and academically challenging curricula,” Powers said. “Attending desegregated schools often facilitates minority students’ access to social networks that provide information and opportunities that help them navigate the educational system.”

Powers also conducted the same analysis for charter schools.

“The patterns for charter schools are those of the state as a whole, except that charter schools as a group are less diverse than public schools,” Powers said.

Another factor contributing to this increased segregation is poverty, Powers said.

“We should not be appalled or shocked in any way that over 59 percent of our kids are minority. We should be appalled that 55 percent of our kids in Arizona – 1.1 million kids in our public schools – qualify for free or reduced lunch,” Scribner said. “Diversity is not the challenge. Poverty is the challenge.”

Students of color are more than twice as likely as White students to attend schools with a large percentage of low-income students, Powers said.

The average White student attends a school that is 36 percent low-income, while the average Latino student attends a school that is 62 percent low-income, Powers said.

When the percentage of minority students at a school is correlated to the percentage of students receiving reduced-price and free lunch, the largest number – “334 schools – or 17.5 percent of Arizona’s public schools serve 80 to 100 percent of poor students and 80 to 100 percent of minority students,” Powers said.

When achievement gaps are correlated with ethnicity and poverty, “there is a huge disproportionality of kids in the poverty sector and that plays a significant part in how we educate kids,” said Dr. Alberto Siqueiros, former superintendent ofBaboquivari Unified School District in Sells, which primarily serves children from the Tohono O’odham Nation.

School segregation in metropolitan Phoenix, which Powers has studied extensively, shows a relationship between school segregation and housing segregation.

“In the absence of public policies that address desegregation, the patterns will likely intensify,” Powers said.

The population shift from the core of Phoenix to the suburbs in the 1980s also played a role, Scribner said.

Location does matter, said Siqueiros, who led the district of about 1,000 students in southern Arizona for five years.

“Where kids reside and what schools they go to creates an opportunity gap,” Siqueiros said. “It’s much more challenging to recruit and hire highly qualified teachers and keep them for the long haul. Wraparound services and the social services needed are fragmented.”

To attract more highly-effective teachers, Baboquivari district raised teachers’ salaries, relaxed the rule allowing teachers new to the district credit for only five years of experience and provided bus service for teachers who lived in Tucson, almost two hours away, to the schools in Sells.

Recent studies of Black students before and after desegregation indicate that desegregation had important long-term effects on their lives by increasing graduation rates and increasing incomes, Powers said.

“The 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. the Board of Education presents an opportunity to reflect on the ways that our schools still remain separate and unequal,” Powers said. “These milestone anniversaries also challenge us to think creatively about how desegregation policies can work with other policies to improve minority students’ access to educational resources and opportunities.”